HOSPITALFIELD RESIDENCY

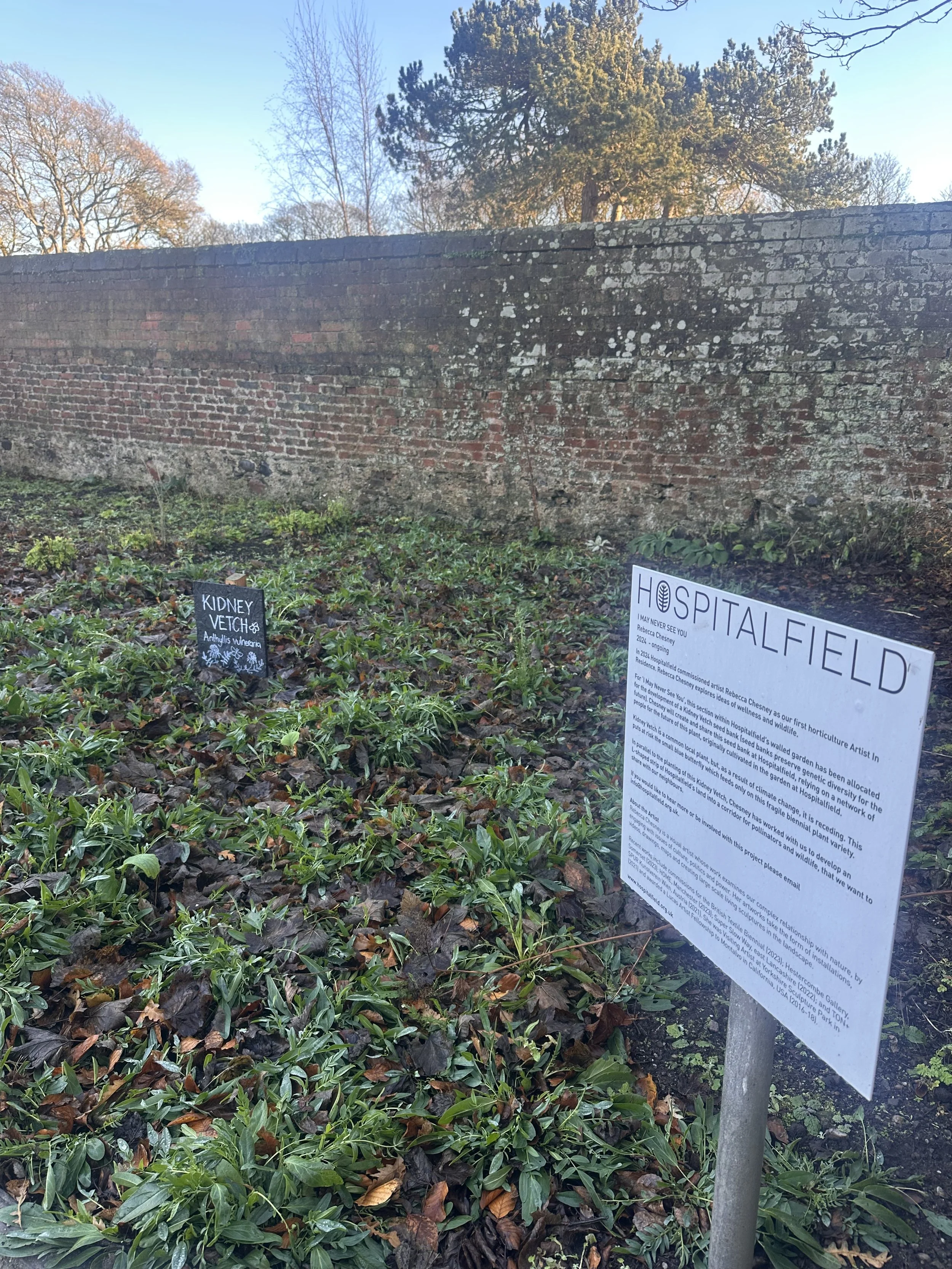

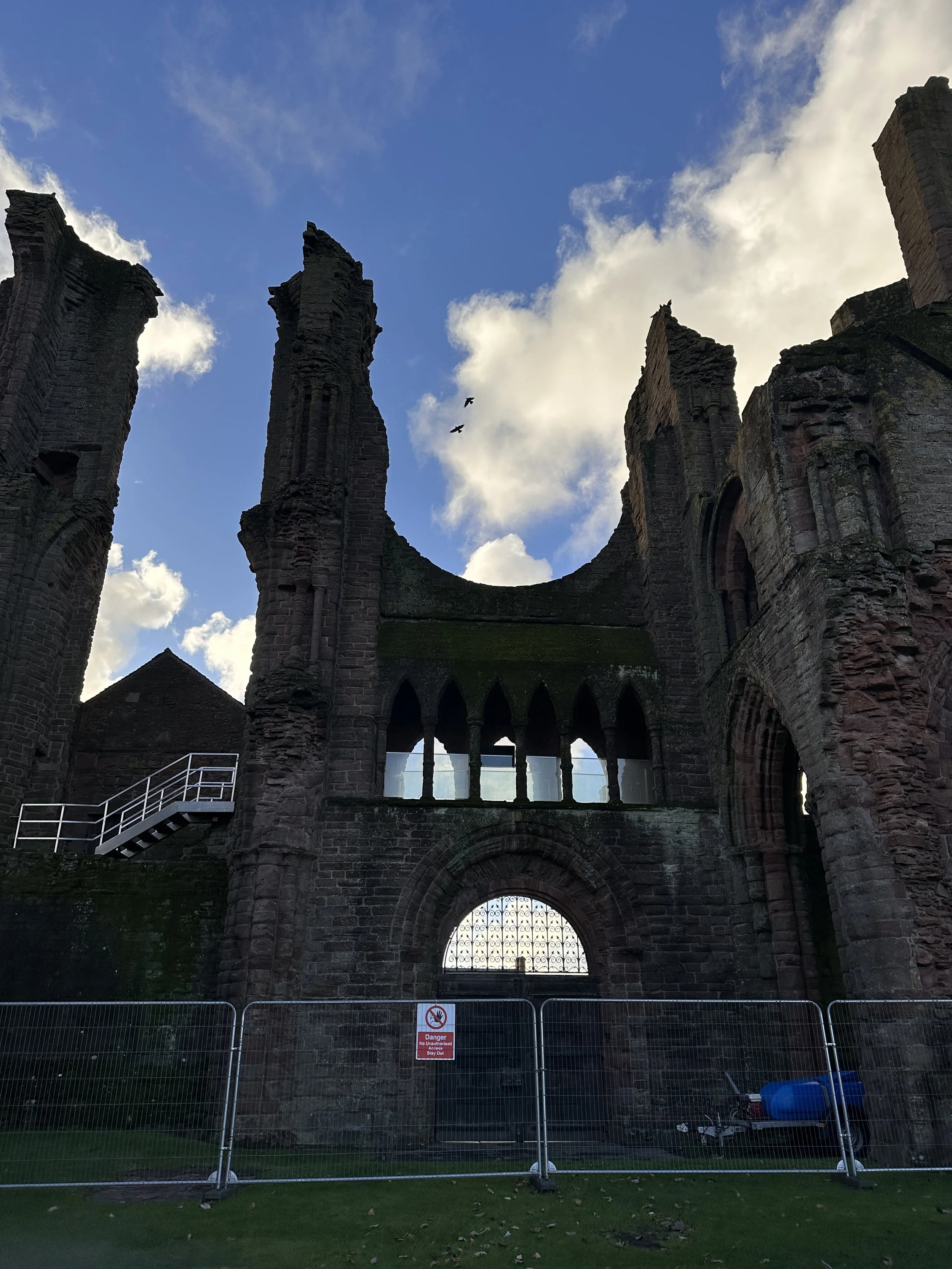

During the Hospitalfield residency in Arbroath, Scotland, my Mapping the Liminal project continued its evolution on cemeteries as evolving cultural landscapes as sites where memory, architecture, ecology, and community life intersect and shift over time.

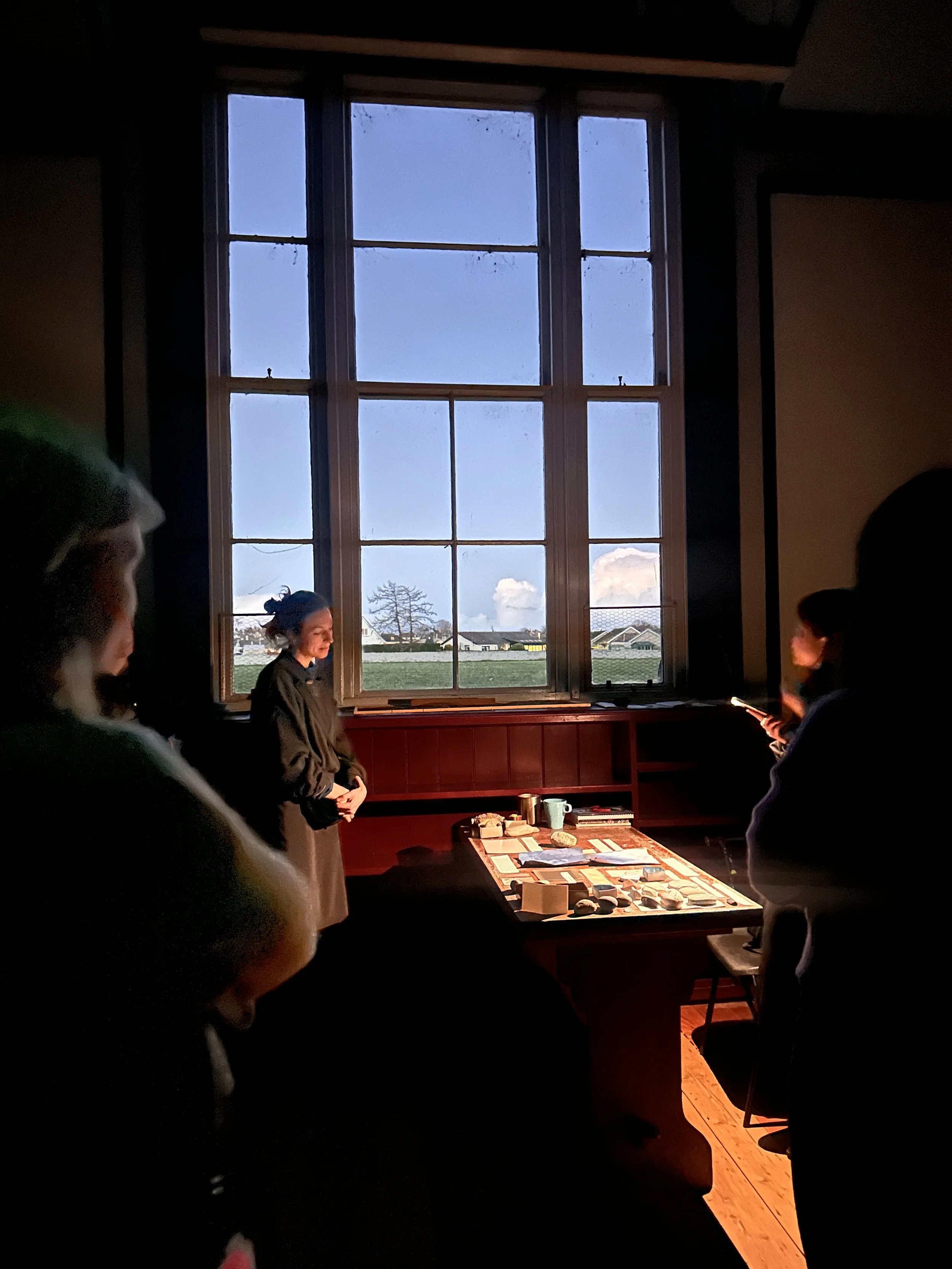

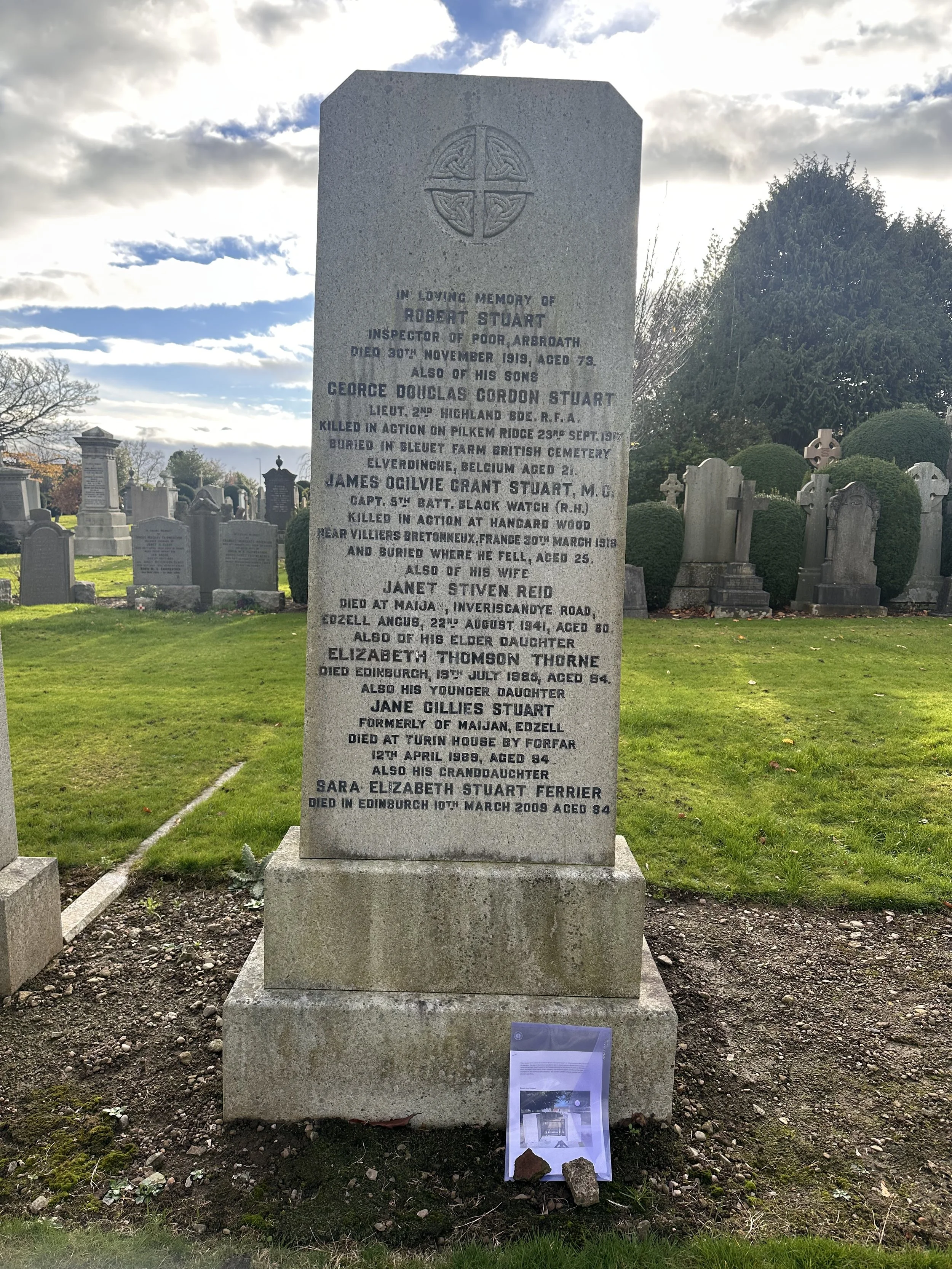

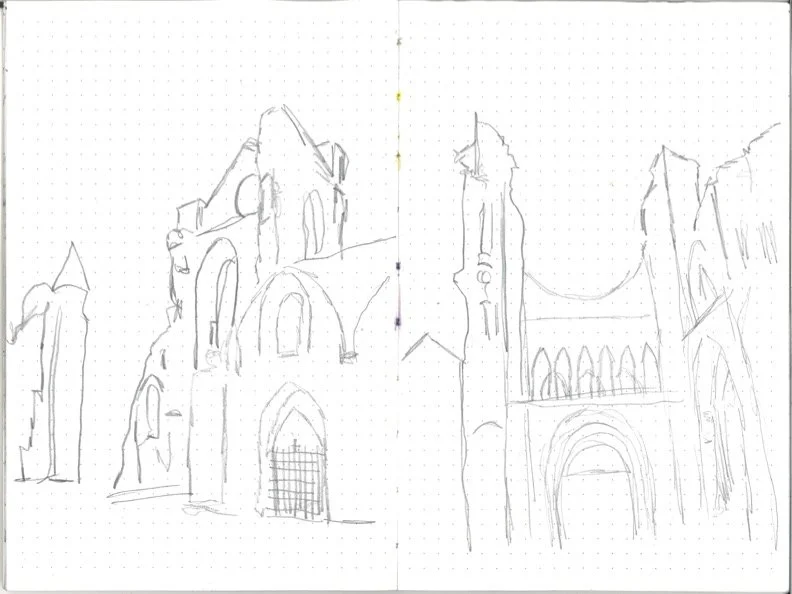

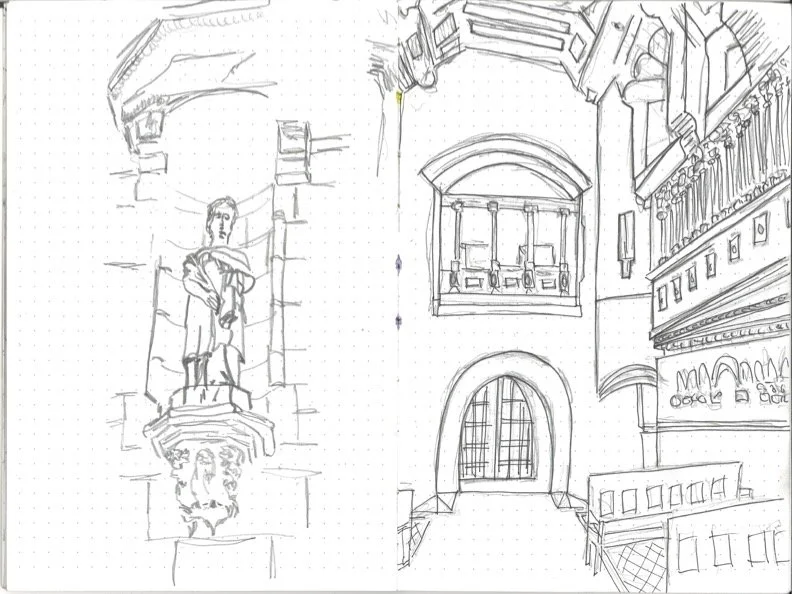

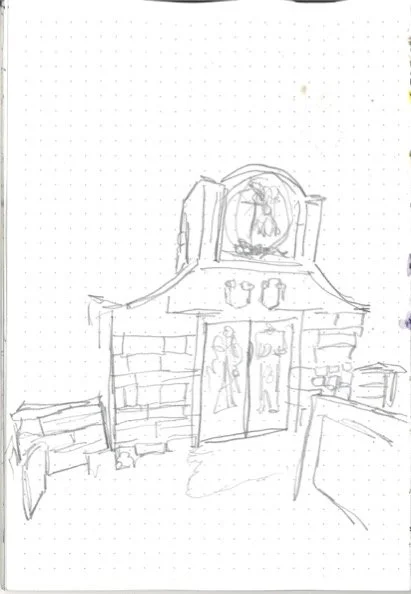

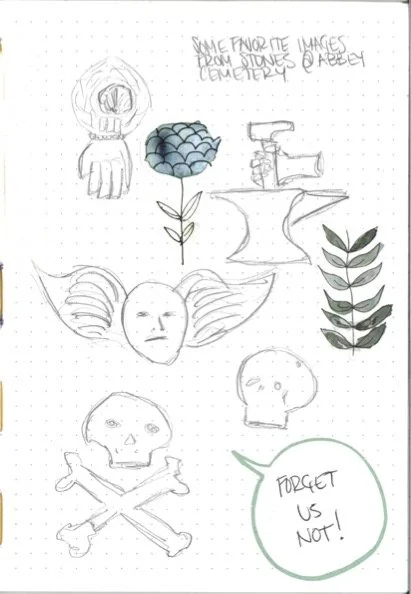

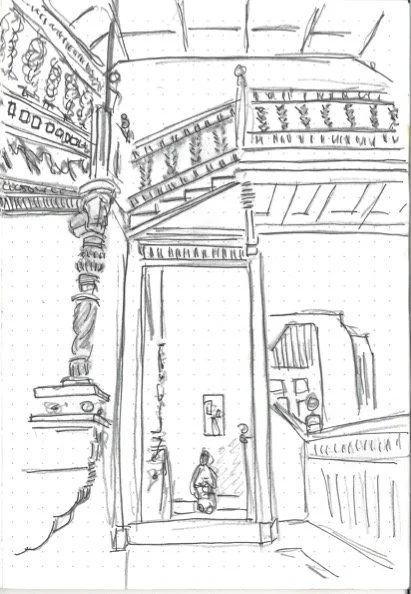

My study in residency centered primarily on the Elizabeth Fraser Mortuary Chapel in Arbroath’s Western Cemetery. This site offered a concentrated lens through which to examine how coastal conditions, local history, and architectural form shape community memory and the experience of mourning in place. The chapel’s architectural expression of mourning, material presence, position within the landscape, and relationship to the surrounding burial ground became key anchors for the research.

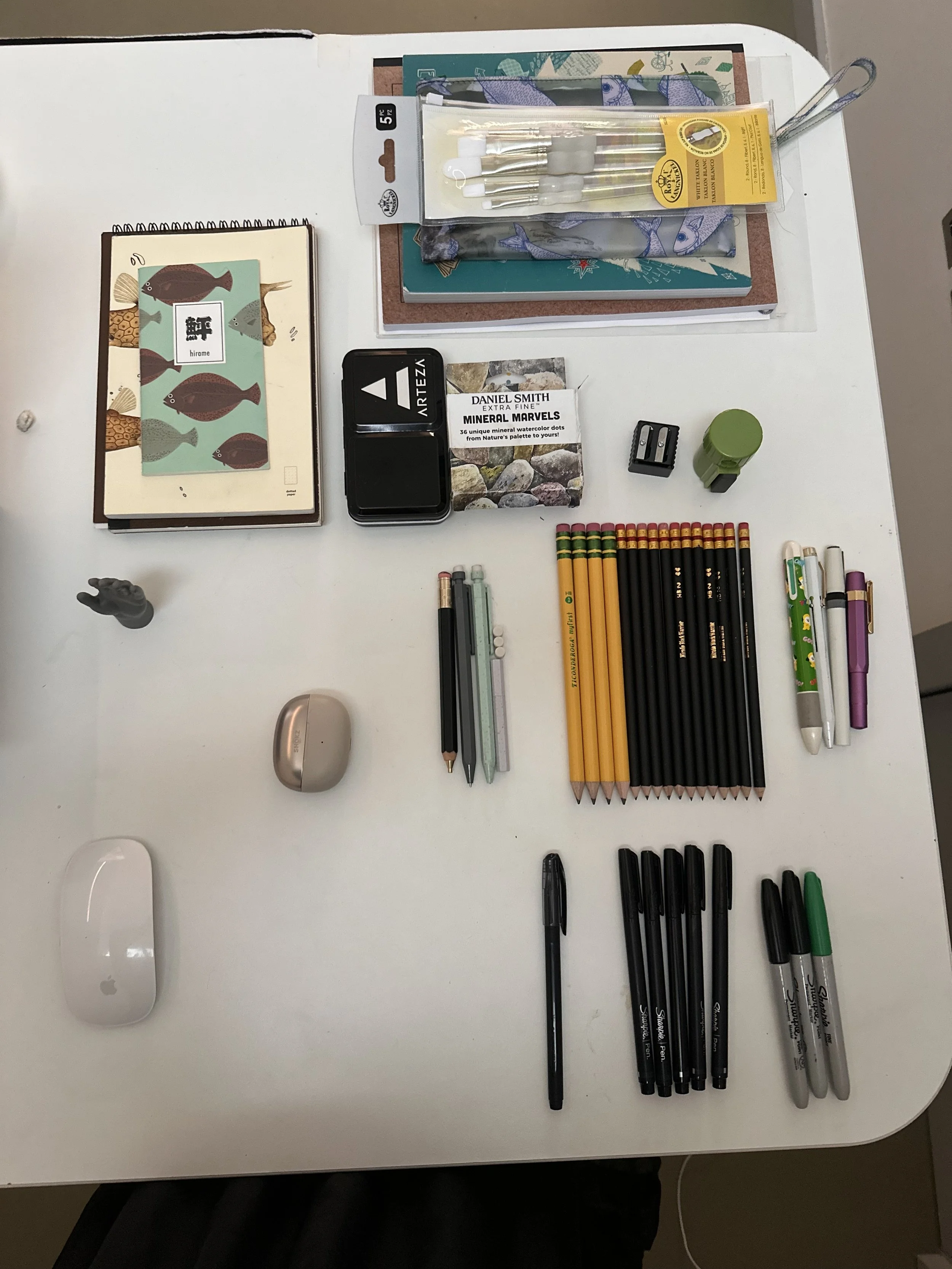

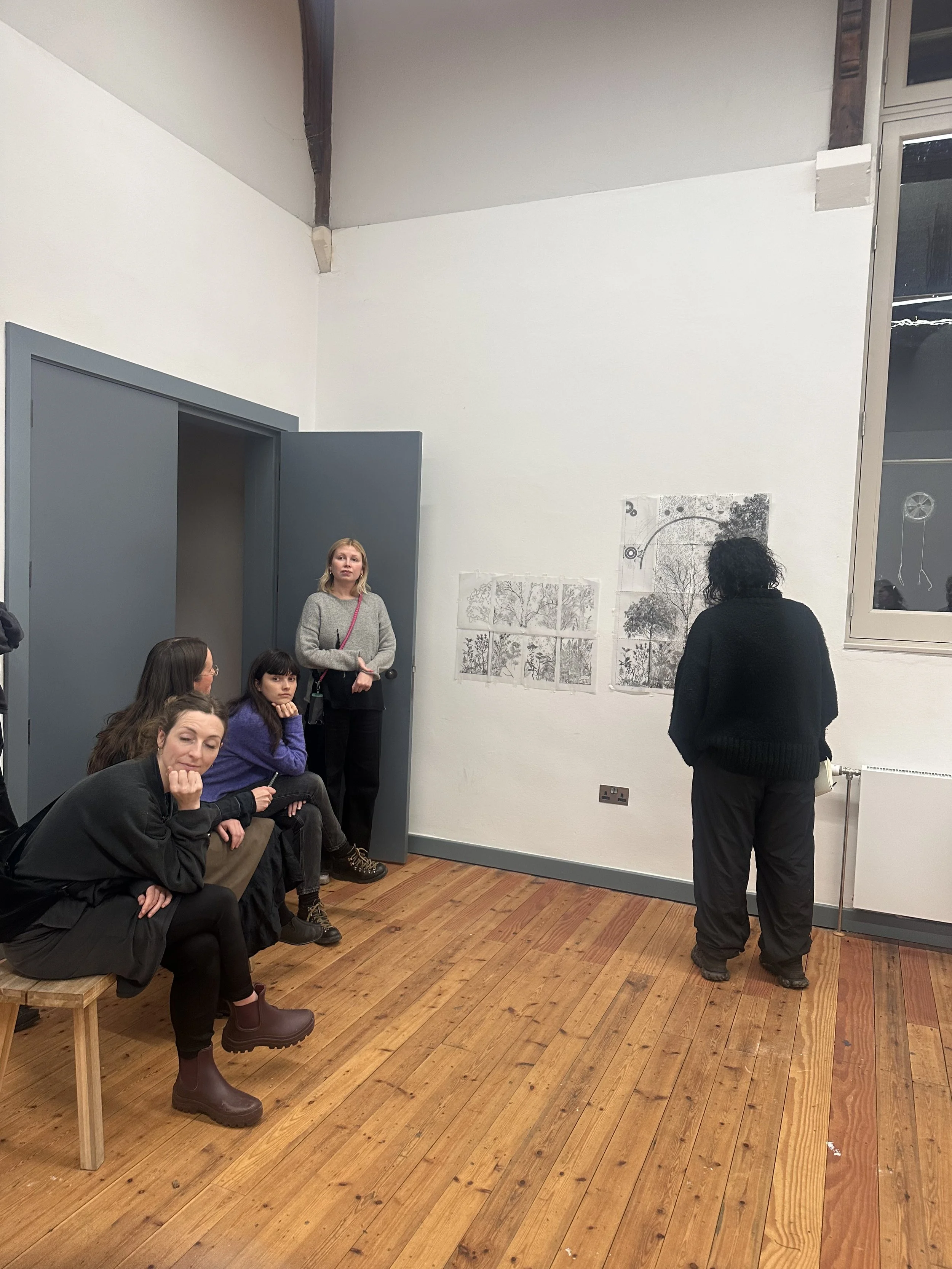

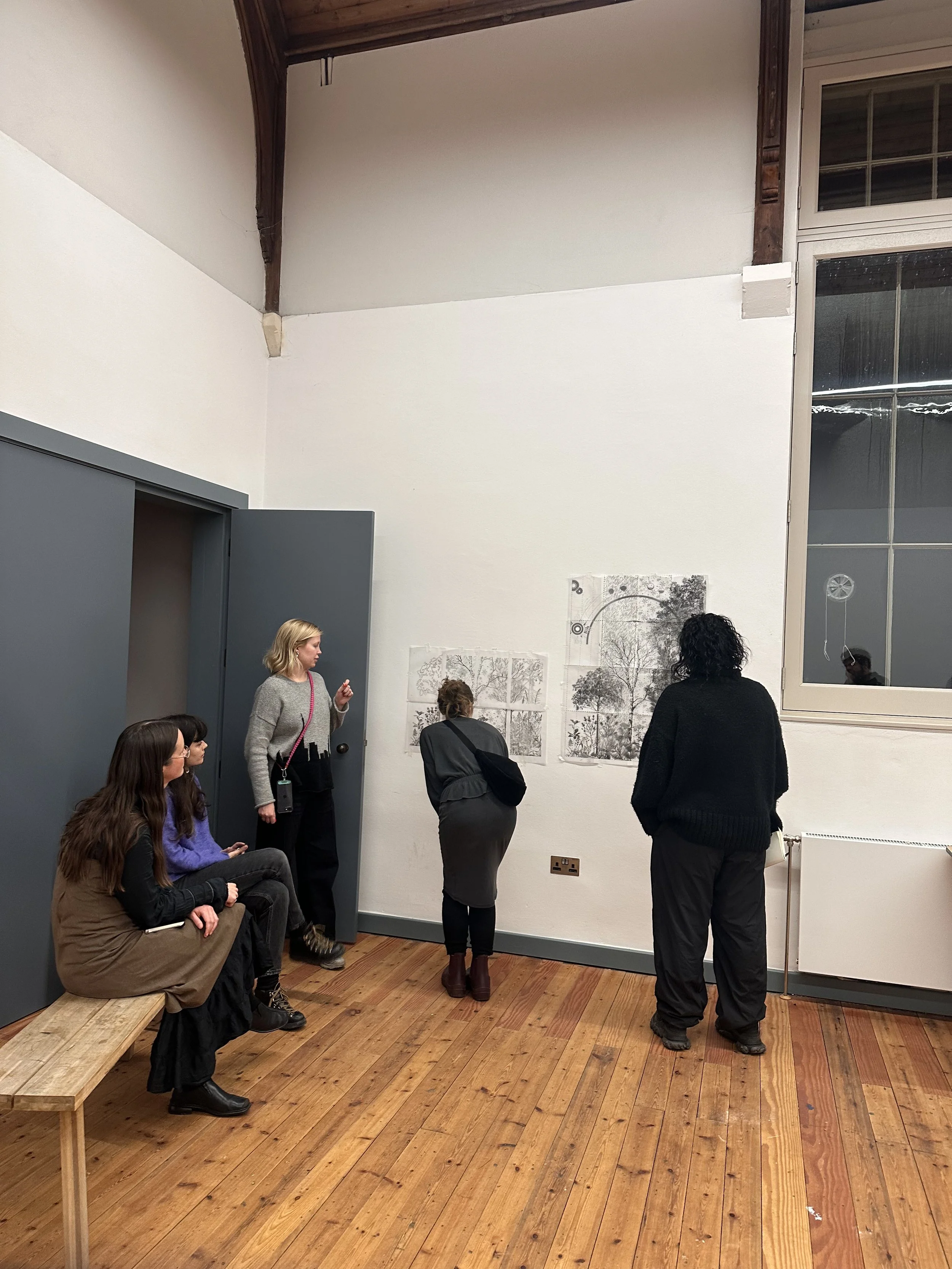

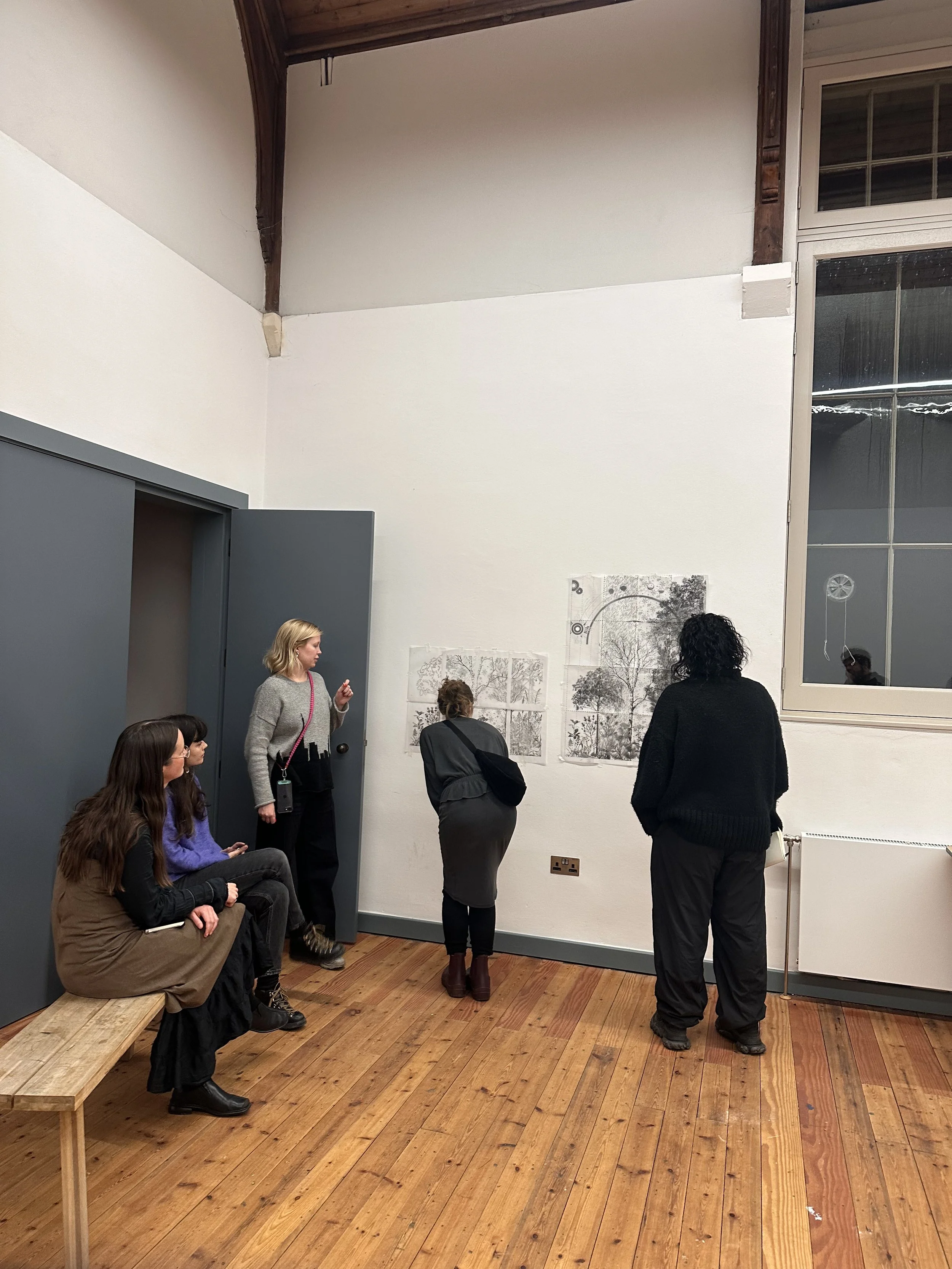

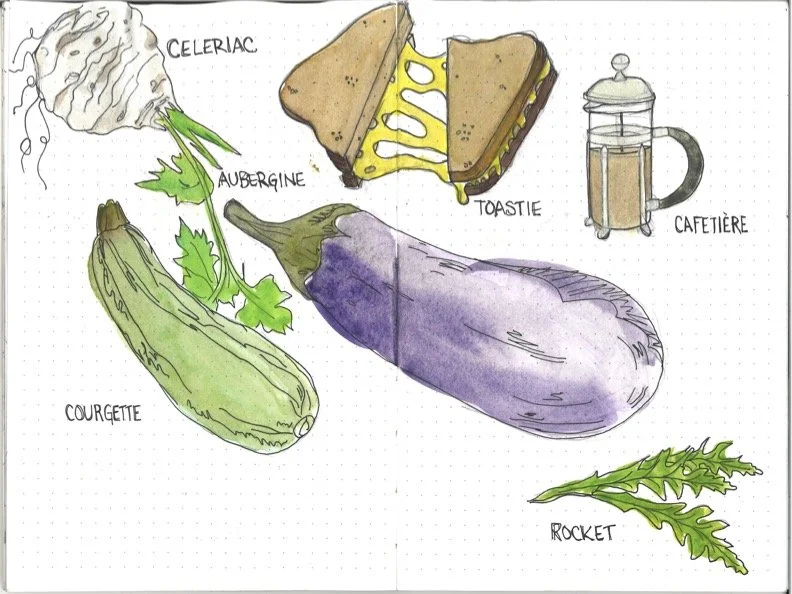

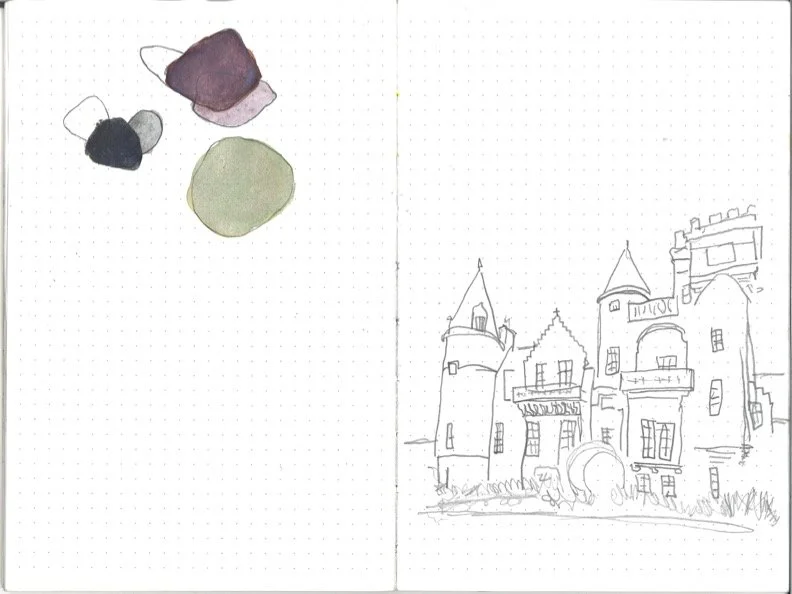

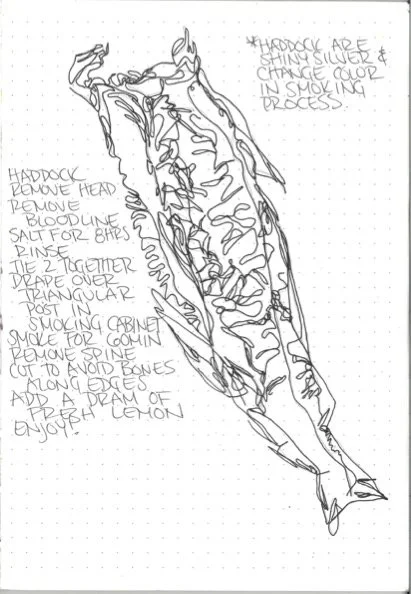

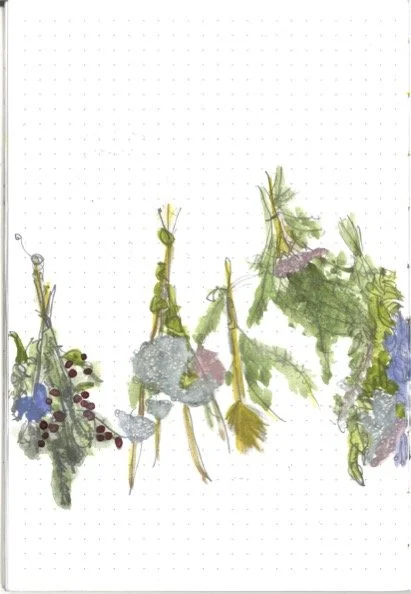

Inspired by both the surrounding landscape and the dedicated studio space at Hospitalfield, the residency also generated a new body of my drawings and paintings. These works served as a way to think through spatial relationships, textures, and atmospheres, using illustration as a form of inquiry rather than final output. Together, the fieldwork and visual studies advanced the broader project on cemeteries as living cultural landscapes and contributed foundational material for the forthcoming Mapping the Liminal book.

A Reflection on Mapping the Liminal after Residency at Hospitalfield

My time in Arbroath has echoed a feeling that recurs throughout my research: some landscapes only reveal themselves through slow, sustained attention. During this residency, the Mortuary Chapel became the place where that practice deepened. Returning to it shifted my understanding of it not as a fixed architectural object, but as an environment unfolding over time.

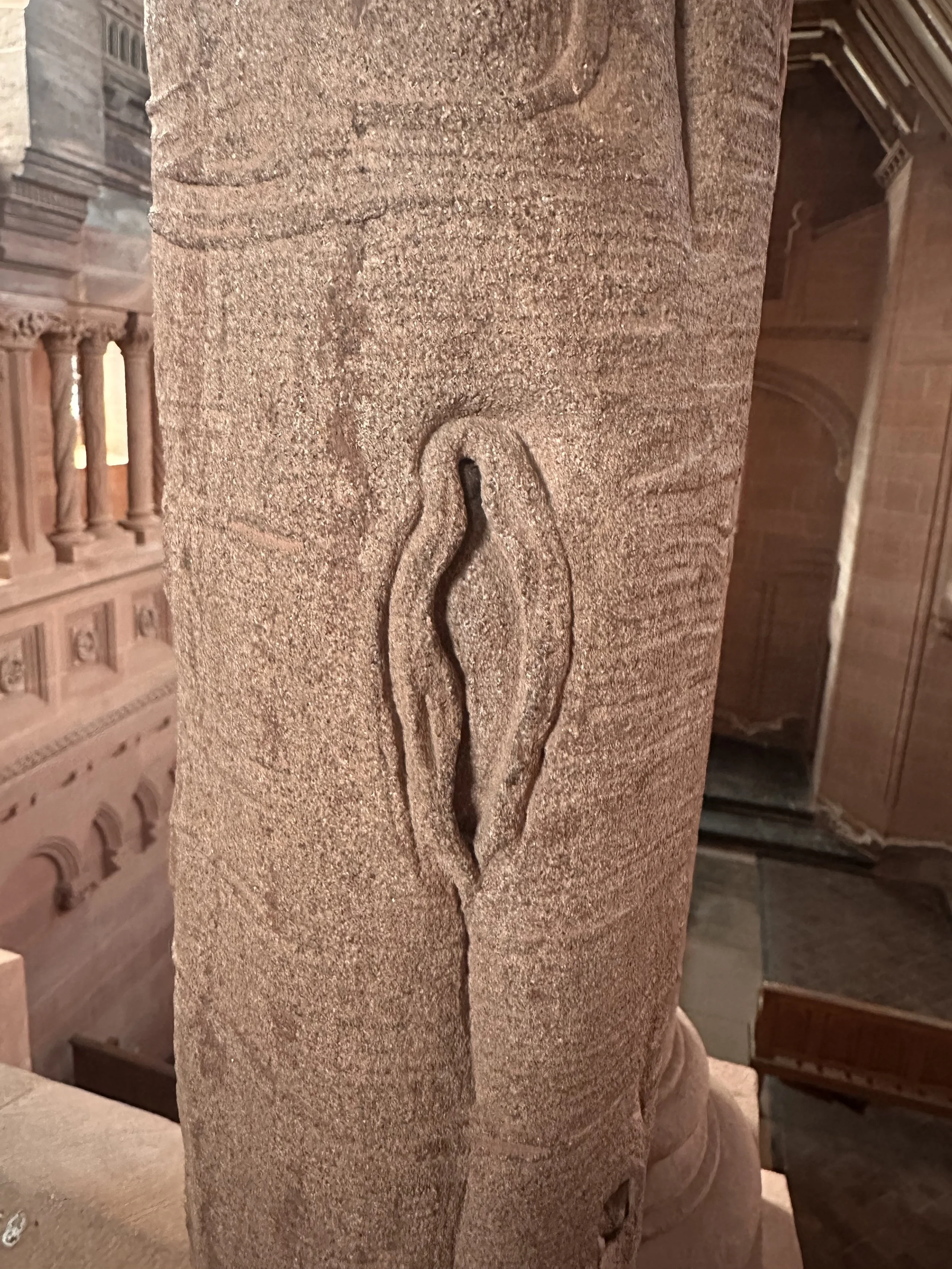

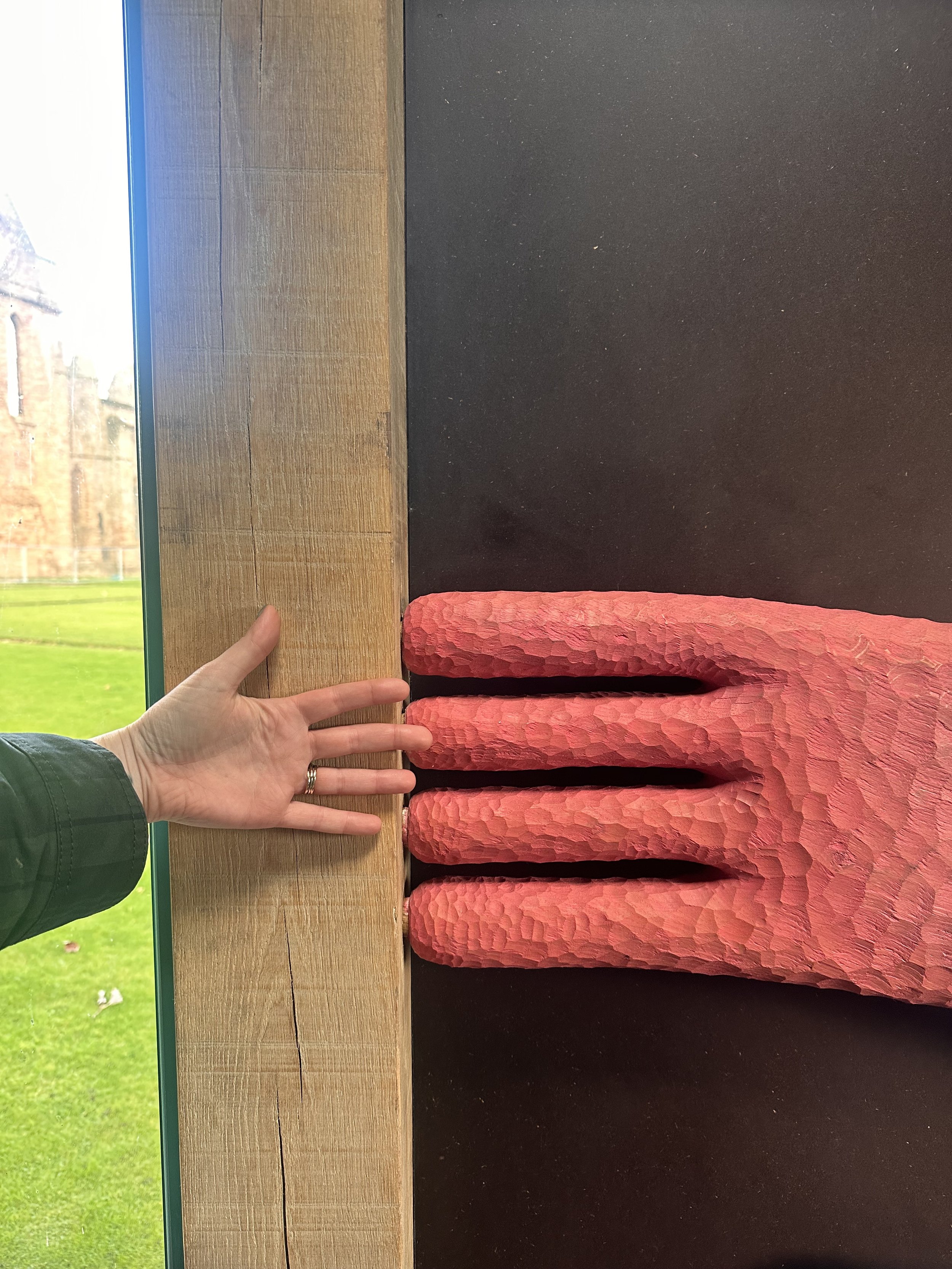

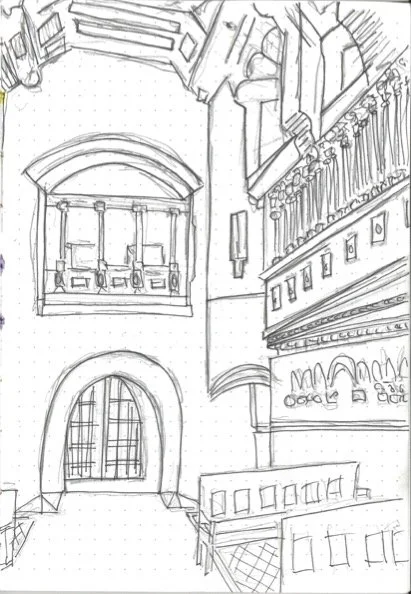

Inside, the cedar roof and sandstone walls create an acoustic hush that makes even small changes feel amplified. I gave hours to drawing as narrow windows cast moving planes of light across the pillars. Sketching the carved foliage, the negative spaces, and the curling shadows allowed me to register aspects of the space that writing alone couldn’t hold. Through drawing, I began to consider how grief seems to hover in the chapel rather than reside only in the stone, and how a building weathered for more than a century can still convey tenderness.

My drawings were never meant as illustrations, they were a method. They slowed me enough to perceive relationships that usually remain invisible. The chapel revealed itself as something shaped not only by design, but by grief, seasonal light, acoustic absorption, and the labor of the local masons who built it. It became clear that the chapel functions as a relational system in which memory, material, and environment continually shape one another.

This practice of lingering has guided my larger project. Each cemetery I’ve studied has its own terms of engagement: the Sugarlands Cemetery in the Smokies, where winter quiet makes family plots feel suspended in time; the Taft burial ground in Pennsylvania, where dams and reservoirs have redefined the landscape around it; Plymouth Meeting Friends Burial Ground, where burial, education, and worship form a continuous social ecology that shaped my childhood; Graceland Cemetery in Chicago, where designed landscape operates as ecological and civic infrastructure; and the Dorotheenstädtischer Friedhof in Berlin, where political and artistic histories converge.

Across all these sites, cemeteries emerge not simply as resting places but as archives of architectural intention, ecological change, cultural value, and lived experience. They blur distinctions between past and present, living and dead, public and sacred. Understanding them requires methods grounded in attentiveness: walking, pausing, drawing, mapping, listening.

Research is not only about gathering information, it is also about cultivating presence. It demonstrates how attention itself can be a form of care, and how landscape can register emotion as powerfully as architecture. This project has become a study of relationships—between people and landscapes, memory and material, observation and interpretation, art practice and geographic inquiry. Cemeteries remind me that to study a landscape is to be shaped by it, and that the work continues through walking, noticing, making, and the slow, deliberate practice of paying attention.

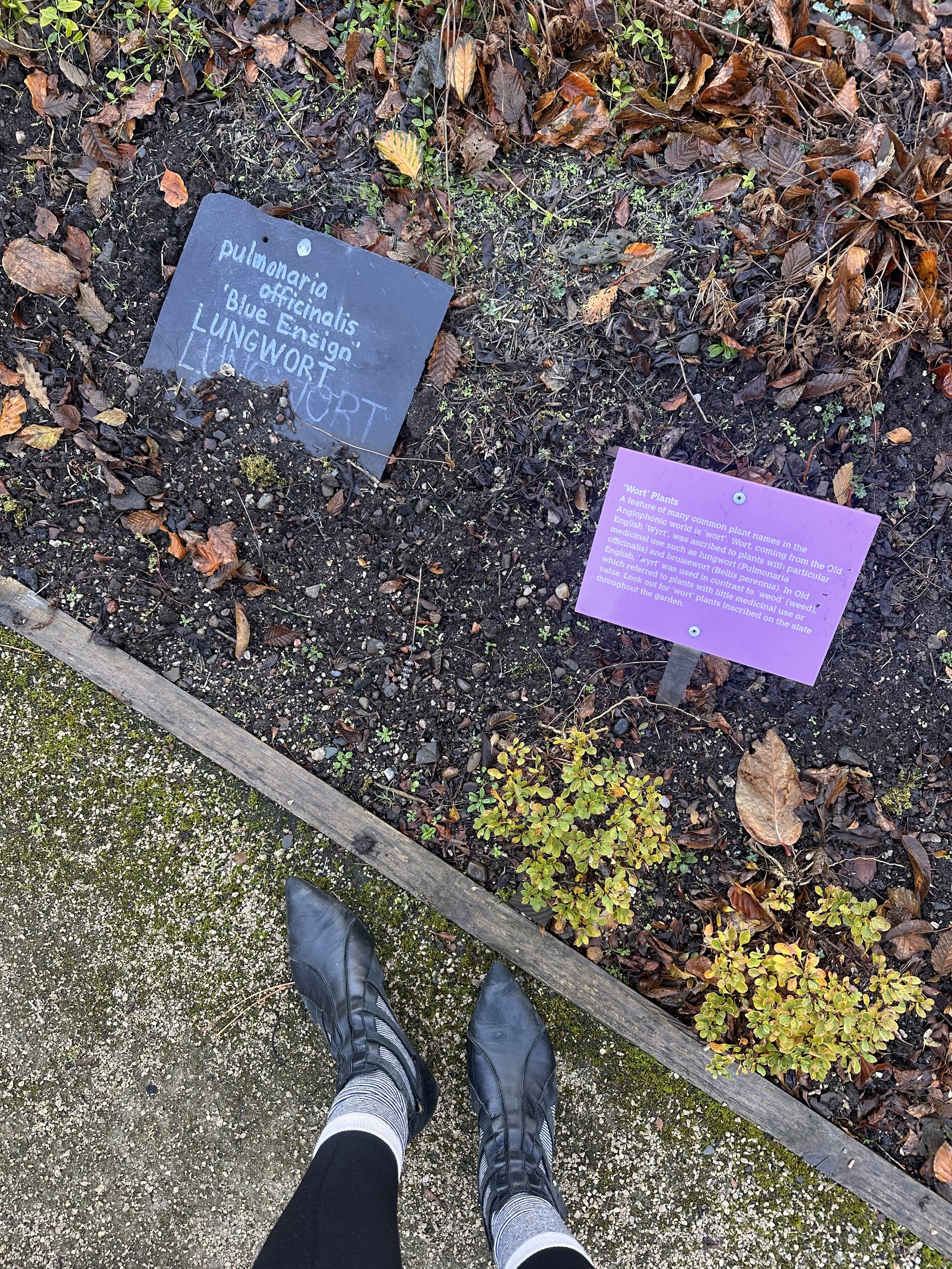

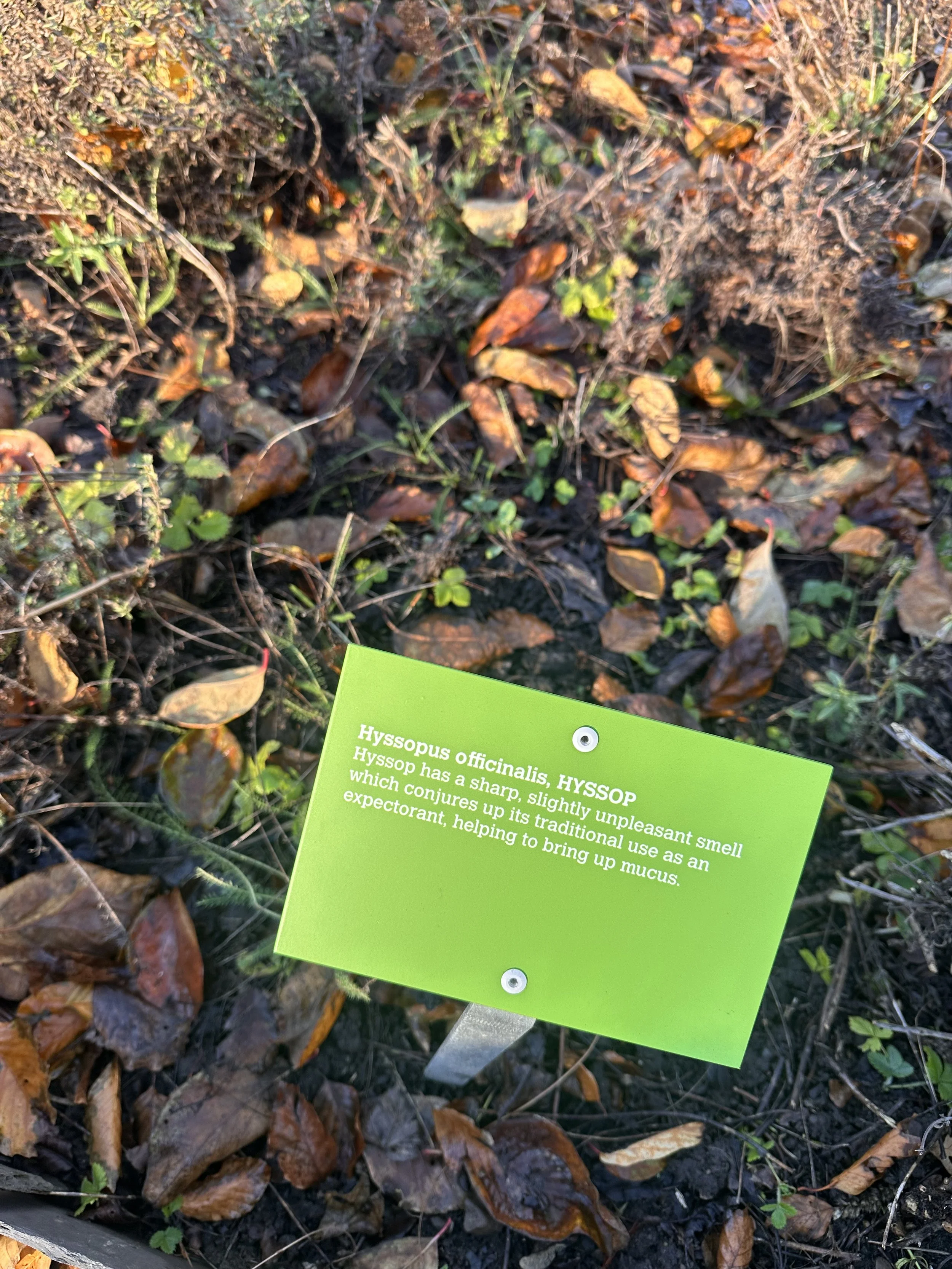

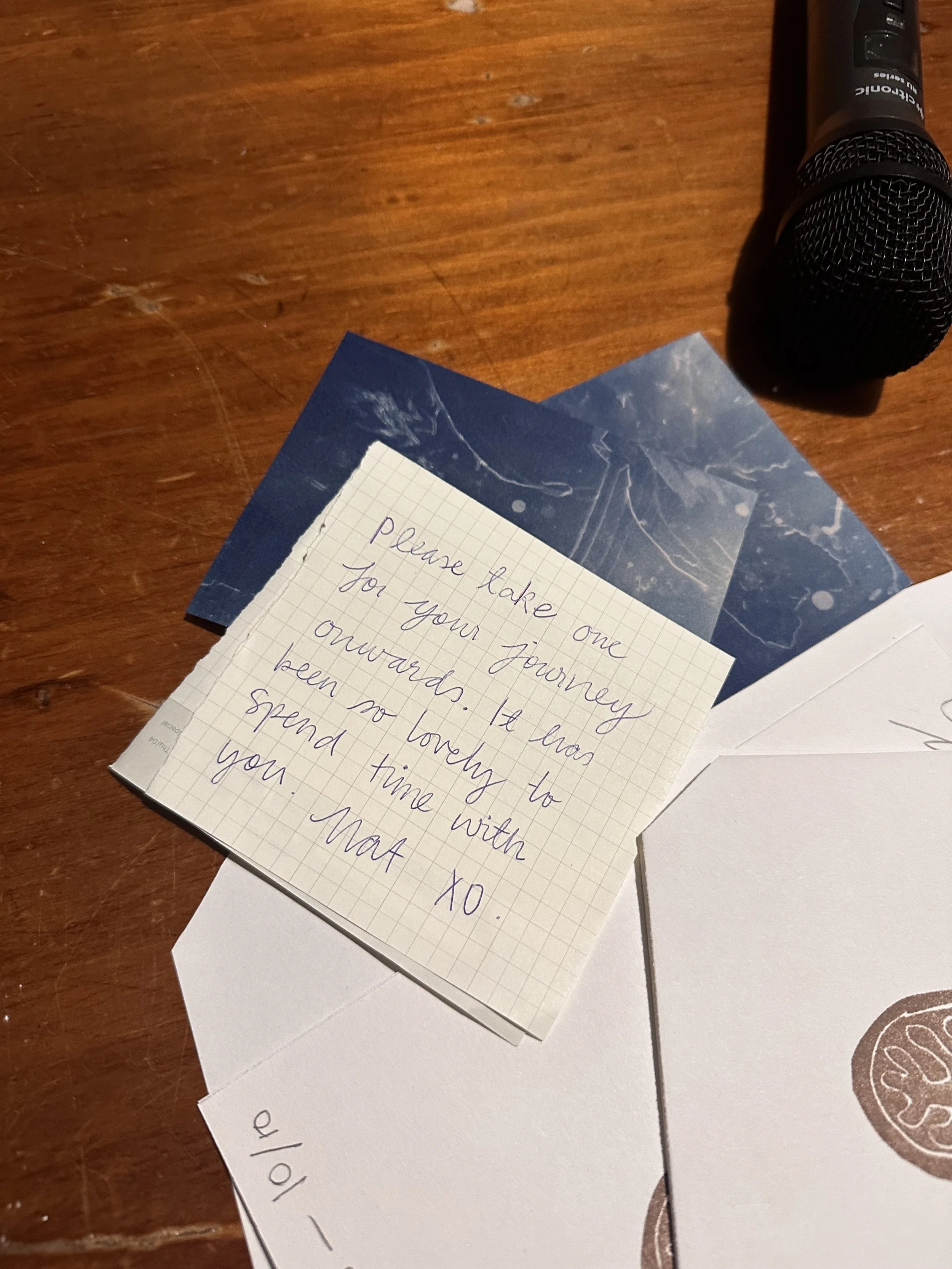

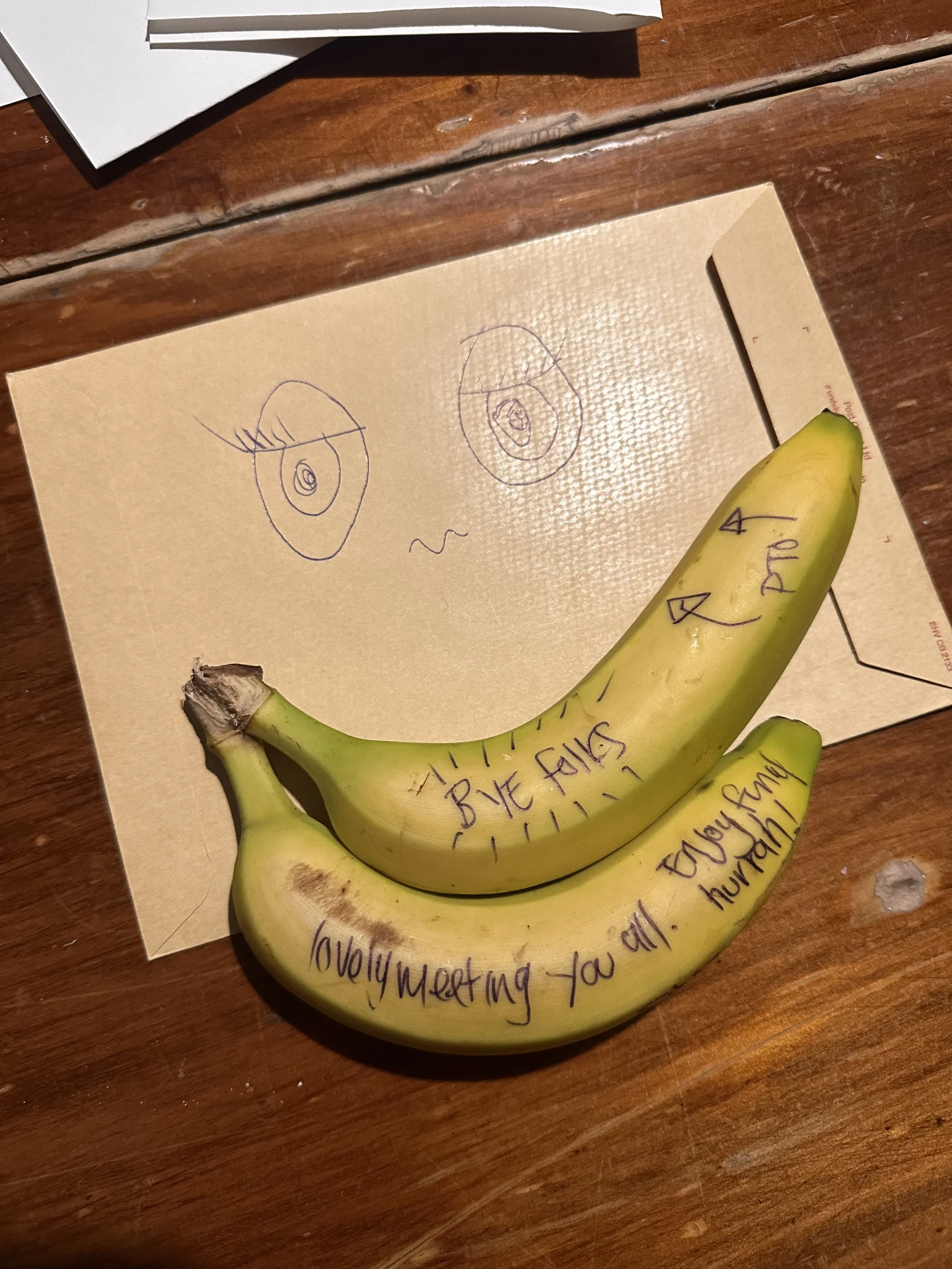

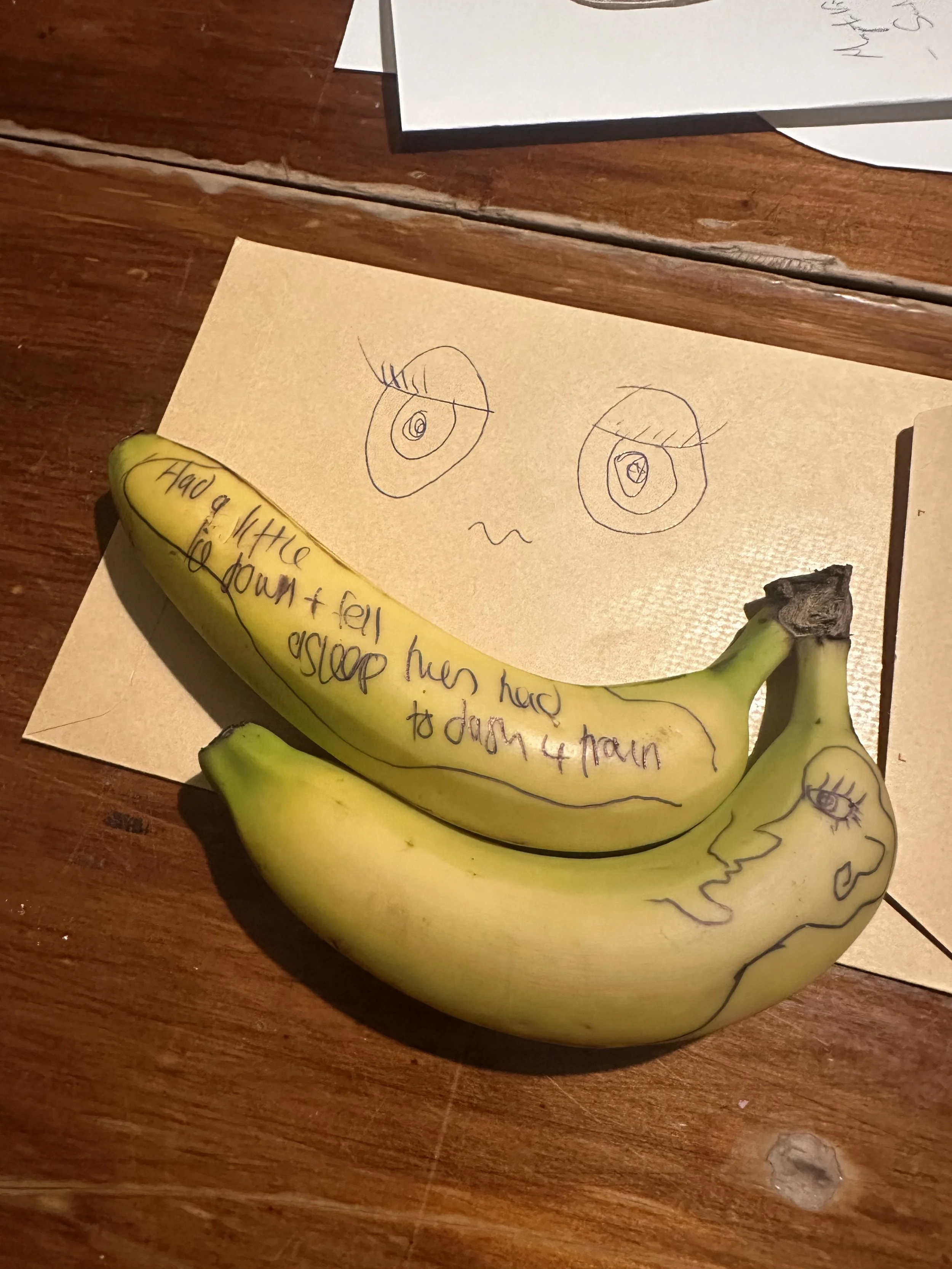

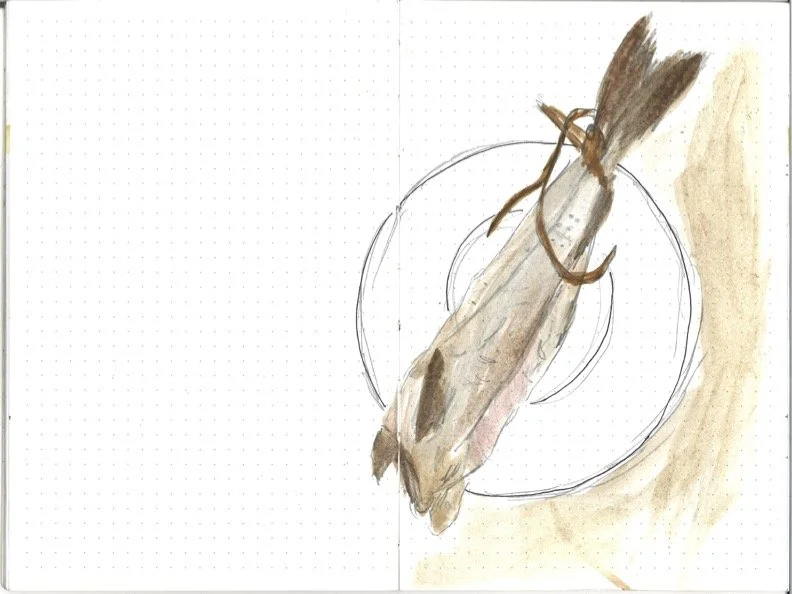

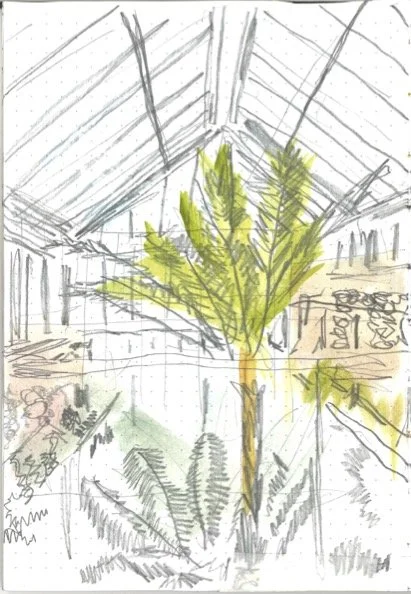

Hospitalfield House, Fernery, Gardens, Kitchen, and Studios

Fraser Mortuary Chapel and the Western Cemetery

Arbroath

Artwork Created at Hospitalfield

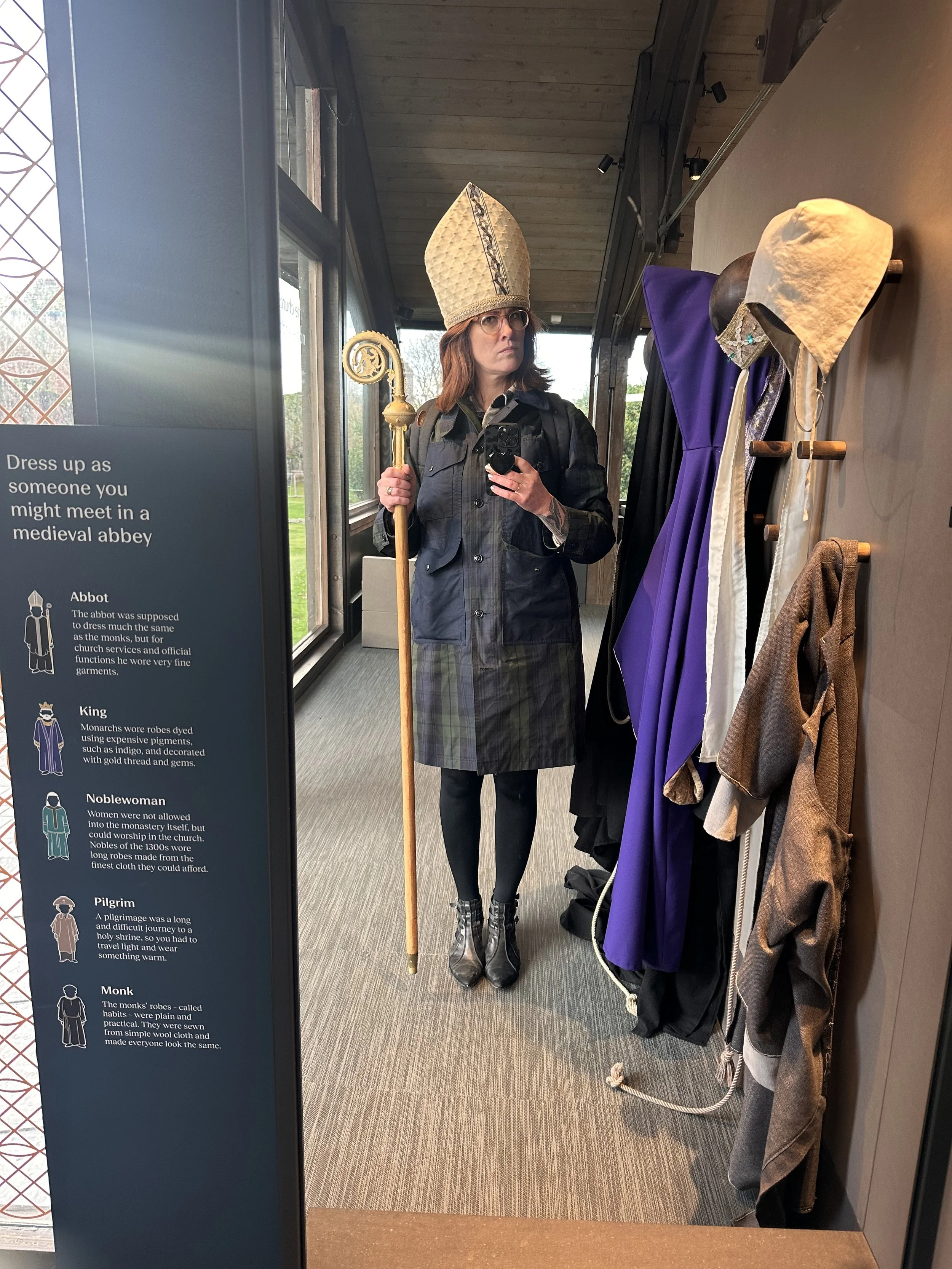

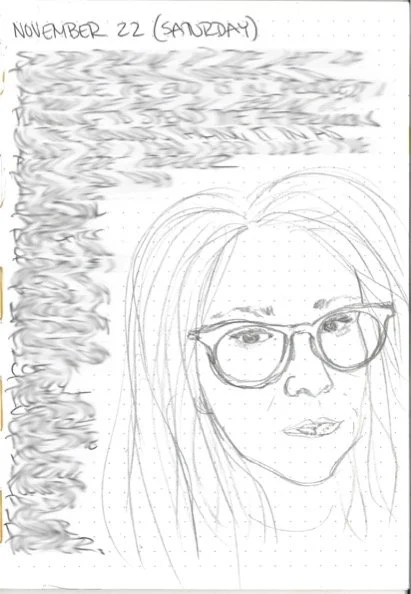

Hospitalfield Mirror Portraits